I documented the eclipse cruise decision making process shortly after the cruise was over based upon

extensive conversations with knowledgeable eclipse chasers on board.

While that documentation relates to cruises, I've read or heard about numerous land tours that have

been inflexible and clouded out, notably Shanghai 2009, where

eclipse climatologist Jay Anderson

issued a strong weather warning nearly a week in advance but few tours took note and relocated. We

expected better from the Travelquest travel company and the

Paul

Gauguin based upon past history but the detail analysis indicates that we were too

complacent.

Eclipse Cruises and How to Improve Them

Prior Experience

2019 was my fourth eclipse cruise. In 2009 I was on

Costa

Classica charted by Roy Mayhugh. The ship left Kagoshima about 45 hours before totality and

arrived in Kobe about 42 hours after totality. The stated objective was the maximum eclipse point east of

Iwo Jima but Roy said with their port schedule that they could work with as much as 1,000 miles of the

path. It turned out that the area around Iwo Jima was quite clear even though the two sea days on the way

to/from the max point were mostly rainy. Costa Allegra was also at the 2009 eclipse but was concluding

its cruise the next morning in Shanghai. Being constrained to a short distance from Shanghai it was

clouded out.

In 2010 I was on the

Paul Gauguin. The eclipse objective was

about 120 miles south of Tahiti. One full sea day was allowed to reach this area from Bora Bora for a

~8AM eclipse. The day after the eclipse we needed to be in Moorea with the cruise ending the morning

after that. At the eclipse there were scattered puffy clouds and the captain had to turn the ship just

before second contact to outrun them. We had two cloudy periods of 20 and 10 seconds within the 4 minute

totality, and everyone heaved a sigh of relief that the last minute maneuvers had been successful.

In 2016 Liz and I were on the

Damai II, a scuba liveaboard in

Indonesia. The travel agent had never seen an eclipse and planned a custom itinerary for her best

customers. Liz and I met her at the Long Beach Scuba Show in 2013 and persuaded her to let us sign up and

be the “eclipse experts.” We saw the ~9AM eclipse just north of the equator near the Goraici Islands,

where we had scheduled diving after noon. We saw weather maps the prior day which suggested that perhaps

we should be farther west and farther from land. The captain responded that “weather maps aren’t very

reliable out here” and stuck to the planned itinerary. In the last hour before second contact we were

in the clear but sailing toward clouds and only temporarily did the captain slow the progress toward our

scheduled afternoon dive sites.

2016 was our first direct realization that eclipse cruises all have a planned itinerary, and the default

position is that itinerary will be followed regardless of weather. We had read of some sad tales in 2012

of ships sailing into clouds and the infamous Pacific Jewel failing to reach totality at all.

For 2019 I returned to the

Paul Gauguin, this time with Liz who

had never been to French Polynesia. Another attraction was the chance to visit Pitcairn Island, which was

not achieved due to ship liability concerns with the clientele in challenging weather. We had no real

concerns about the capability to chase the eclipse. Paul Gauguin had successfully viewed 4 prior

eclipses. All of these cruises had been chartered by Wilderness Travel and Travelquest. Travelquest

specializes in astronomy travel and its president had 17 successful eclipses without a miss. Noted

climatologist Jay Anderson is retained by Travelquest to assist in planning itineraries and provide

weather forecasts leading up to the eclipse.

Paul Gauguin 2019 Eclipse as

Experienced by Passengers

The three sea days on the way to Pitcairn and June 30 at Pitcairn were consistently overcast with

occasional rain. Though Pitcairn is 23 degrees latitude the ocean temperature was a chilly 66 F vs. 80F

in the Society Islands at 17 degrees. The original plan was to stay at Pitcairn through the next morning,

then move over the next 20 hours to the eclipse path. In 2017 that point on the Travelquest website was

NW of Pitcairn past Oeno Island but on the cruise the map showed a point due west and farther from

Pitcairn.

During the afternoon at Pitcairn the captain, the astronomers and trip leaders examined weather forecast

maps for the eclipse that showed a wide band of solid overcast centered at Pitcairn’s latitude. The

ship needed to leave Pitcairn soon in order to reach the eclipse path beyond the wide band of thick

clouds. The ~550 nautical mile distance was about the same to the SW or the NE. A move to the NE would

mean skipping the half day port call in Rangiroa on July 5 and probably the July 6 port call in Bora

Bora. So at 4:30PM on July 1 the astronomers announced that we were going to the SW. The target for the

eclipse was to each 27 degrees 52.7’ S, 140 degrees 00.5’ W by 8AM July 2, and to view totality there

at 10:13AM.

We heard that Jay Anderson was on the road in Chile with another Travelquest eclipse group on July 1 and

not reachable during the 2-3 hours that the decision was made to go SW rather than NE.

On the morning of July 2 there were westerly winds of 30 knots. Thus at about 7AM the captain slowed the

ship to 5 knots to lessen the winds on deck where people were already gathering. At 9AM first contact the

sun was in clear view in a hole even though it was only 9 degrees up and in general there was thick cloud

up to 15 degrees and broken cloud up to 30 degrees above the horizon. Most of us were not that concerned

because we figured last minute maneuvers as in 2010 could find a break in the broken cloud layer. Shortly

after first contact the captain turned the boat 180 degrees to sail at 5 knots with the wind to make the

viewing deck more comfortable.

What most of us passengers did not think about was the cooling effect of the eclipse itself. About 15

minutes before second contact the clouds practically exploded upward and soon we were in at least 90%

cloud cover. Some passengers were observing a bright spot on the horizon but it was then too late to

chase it. The heavy overcast lasted 20-30 minutes past third contact, then gradually retreated to a

similar level of cloud as around first contact.

Post Mortem of the Paul Gauguin

Eclipse Chase and Decision Points

This cruise was well populated with veteran and knowledgeable eclipse chasers. At least two of them were

examining weather maps independently. With 8 more days on the cruise there were many discussions and

questions raised. When and how might different decisions have been made? I’ve already said I was too

complacent from past experience, and I believe that was true for many people including the decision

makers. There have been “close calls” before as in 2010, but the decision process was perhaps not

reviewed then as we hope it will be now.

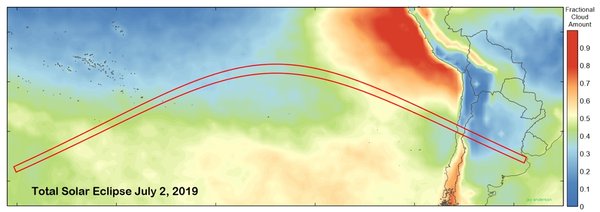

Climatology:

Jay Anderson’s July winter weather maps for the Southern Hemisphere are quite consistent. The higher

the latitude, the greater the average cloud cover.

Thus I found it puzzling on the cruise that the original plan to view the eclipse NW of Oeno was changed

to a higher latitude due west of Pitcairn. What’s not on average cloud charts is the cooling effect of

the eclipse itself. The cooling can be a positive effect in tropical climates by reducing heat

convection. But with 66 degree water and being just past a heavy cloud layer, perhaps the likelihood of

the eclipse cooling generating more clouds should have been anticipated. Surely this is a greater danger

at 27 degrees latitude to the SW of Pitcairn than at 20 degrees latitude to the NE with air and sea

temperatures 10C warmer.

Meteorology and the NW vs. SE decision at Pitcairn:

The ability to acquire and analyze a lot of data by satellite on board ship is limited. There needs to be

land based backup to do that. It’s not reasonable to expect Jay Anderson to do it when he’s on a

different trip with intermittent access to South Pacific weather data. And on the ship we had two expert

astronomers but they are not meteorologists. A trained meteorologist might have known the dangers of

eclipse cooling but most of us never considered it until we saw it happen so dramatically.

Weather Observation: How Soon Before the Eclipse Could Clouds Have Been

Avoided?

Weather maps have been analyzed after the fact. The eclipse cooling can be identified in some of that

data. There were some holes in the clouds at the time of totality where humidity was lower. The estimate

is that a low humidity area needed to be identified 90-100 minutes in advance for the ship to change its

heading and make it there on time. This is another situation where the data needs to be collected on land

to be timely, with frequent updates being communicated to the ship.

What actually happened was that the

Paul Gauguin moved back and

forth in close proximity to the 27 degrees 52.7’ S, 140 degrees 00.5’ W target location that had been

set 40 hours earlier at Pitcairn. No attempt was made to chase brighter horizons and it seems very likely

that the decision makers were as surprised by the eclipse cooling effect upon the clouds as most of us

passengers were. It also seems likely that the decision makers had no information in the hours before

second contact that there might be better options than the target set 40 hours before.

Later in July Joe Rao published on the Solar Eclipse Mailing List how he, as on-board meteorologist in

1991, consulted at dawn with a land based meteorologist in Honolulu to move two cruise ships into a hole

among the widespread clouds near Hawaii's Big Island. Those ships headed for that hole after dawn at

full bore speed of 26 knots. This is exactly what should have been done on the

Paul Gauguin but we had neither on-board or real-time land based

meteorologists available to make the attempt.

We have also learned that the

Paul Gauguin 2010 eclipse cruise

was a closer call than necessary. The ship was in quite clear skies at first contact but sailed to the

exact coordinates planned in advance and in this case printed on commemorative T-shirts. This brought us

into clouds, lost 30 seconds of totality and could have been more if not for last minute evasion.

Cruise Mobility, Is Reality Short of Expectations?

I would say first that the communication between trip leaders, astronomers and ship captains needs

improvement. The situation of sailing to exact coordinates set in advance has been a recurring problem on

many eclipse cruises including three of the four I have been on. Those coordinates should be viewed as a

first cut, a suggestion not an order. The absolute priority should be avoiding clouds and a trained

meteorologist/weather observer should be making those calls. Analyzing weather maps in the last few hours

should be part of the process, probably with land based support having a fast internet connection. Direct

observation/chasing holes or chasing the clear area you are already in applies to the last hour or two,

not just the final minutes. It’s even OK not to be on the centerline and lose 15 seconds of totality to

stay away from the clouds.

An Itinerary Not Optimally Planned for Eclipse Success

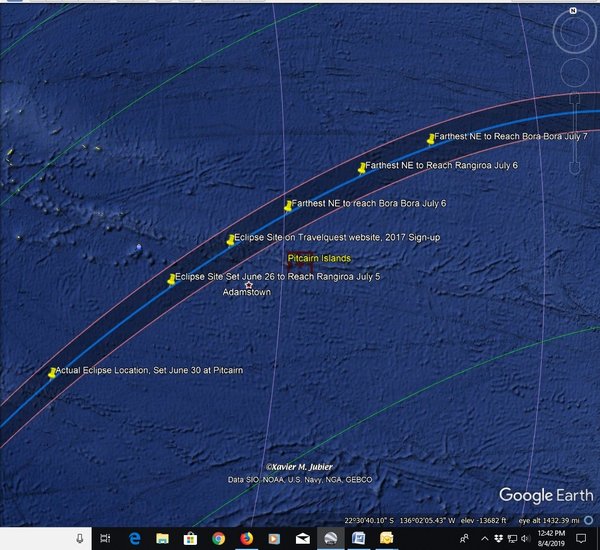

When we signed up in 2017 the viewing spot was shown on the TQ website as the shortest distance to the

centerline from Pitcairn. That’s about 23d 30’ S, 130d W. That gave the impression we could move

either way to chase clear skies. See attached Jay Anderson map of July cloud cover climatology. The only

land speck within totality in the Pacific is Oeno Island, which is on the border between the blue (better

odds of clear skies) and green (more tossup odds of clear skies). Advance planning should have picked a

spot or have been prepared to move to the NE rather than SW of Oeno/Pitcairn.

When we got on the ship the viewing spot was due west of Pitcairn, about 24d 49’ S, 133d 39’ W. Why

was it changed? It turns out that point is the easternmost from which we can reach Rangiroa by early

morning July 5. It seems Travelquest/Wilderness Travel didn’t figure this out until well after they

sold the cruise.

I measured distances from Rangiroa and Bora Bora to various eclipse points, because it’s clear now

those were the key constraints how far NE we could go to chase the eclipse. From Tahiti to Pitcairn we

took 81 hours averaging 14.58 knots. From Pitcairn to our eclipse viewing spot we took 39 hours averaging

14.41 knots. Accordingly I calculated hypothetical viewing points farther NE on the eclipse centerline

assuming a speed of 14.5 knots, with the following results.

1) We can skip Rangiroa but make Bora Bora July 6 from 22d 22’ S, 128d, 13’ W. This is only 185nm

from Pitcairn, not nearly far enough to get out of the cloud band we faced.

2) We can make Rangiroa July 6 (meaning Bora Bora port call is July 7) from 21d 00’ s, 124d, 53’ W.

This is 377nm from Pitcairn.

3) We can skip Rangiroa but make Bora Bora July 7 from 19d 49’ S, 121d, 42’ W. This is 547nm from

Pitcairn, the desired distance based upon information we had June 30.

I believe the cruise itinerary was poorly planned. From the beginning an extra sea day after the eclipse

should have been scheduled in order to allow the ship to reach the lower latitudes with better weather

prospects and longer totality. This could have been done by:

1) Making the cruise 15 days instead of 14, or

2) Dropping one of the lesser ports Huahine or Tahaa from the itinerary. Paul Gauguin cruises that go to

the Marquesas usually have an abbreviated itinerary in the Society Islands.

Summary

For the

Paul Gauguin 2019 eclipse cruise I believe there were

issues of complacency and project management, with the most conspicuous examples cited above. I’m sure

the decision makers are motivated to improve the planning and process in the future.